Collection

- Rembrandt

- Impressionism & the École de Paris

- The Birth and Development of Abstract Art

- From Dada and Surrealism

- Joseph Cornell: Seven Boxes

- Mark Rothko’s "Seagram Murals"

- The Painting and Sculpture of Cy Twombly

- From Abstract Expressionism to Minimalism

- Frank Stella’s Artistic Quest

- Japanese Contemporary Art

From our diverse collection of artworks mainly from the 20th century,

we introduce the main artists, their works and the characteristics that define them.

1635, 76.0 × 63.5cm, oval

Rembrandt van Rijn,

Portrait of a Man in a Broad-Brimmed Hat

Gallery 102 ─ Rembrandt

The great Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) is known for a style that made masterful use of Baroque chiaroscuro in paintings of great psychological depth. His paintings take subjects from mythology and the Bible, and he is also celebrated for his work in portraiture and group portraits. In the early 17th century, Amsterdam was at the height of its prosperity as a major center of foreign trade in Europe. After moving to Amsterdam in 1631, Rembrandt painted many portraits of the city’s wealthy merchants, leaders of the church and government officials. This is one such work, and from the man’s apparel it can be assumed that he is one of the city’s wealthier citizens. The light that falls on the model’s face from the left shows his lively expression with rich contrasts of light and shadow and accentuates the impeccable skill and detail with which the artist depicts the texture of the skin and beard, the hair and lace collar and the black fabric of his clothes.

Today we know that this portrait was originally painted as a pair with a portrait of the man’s wife and the two paintings undoubtedly hung together in their home until they were eventually separated in the handling of the family’s estate by later generations. The wife’s portrait is the work titled Portrait of a Lady (1635) now in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art in the U.S. And this work Portrait of a Man in a Broad-Brimmed Hat in the Kawamura collection is one of the few Rembrandt oil paintings in Japanese public collections, along with the work Self Portrait in the collection of the MOA Museum of Art and A Biblical or Historical Nocturnal Scene in the collection of the Artizon Museum.

At the Kawamura, Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Man in a Broad-Brimmed Hat is displayed separately in its own alcove to help museum visitors appreciate the different artistic style and flavor it has from the other modern paintings in the collection.

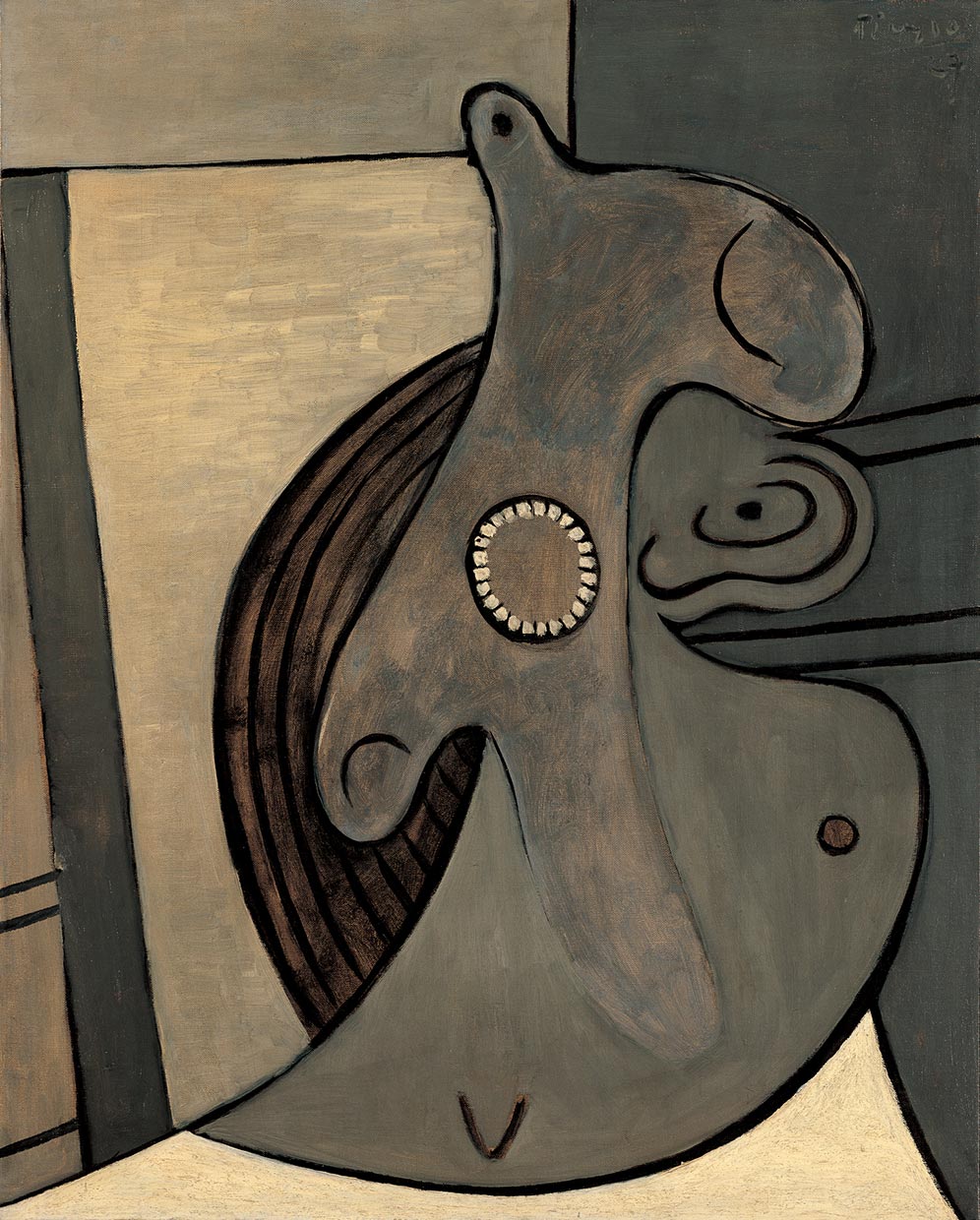

© 2024 - Succession Pablo Picasso - BCF(JAPAN)

Impressionism & the École de Paris

Gallery 101 ─ From Impressionism to the Ecole de Paris

Claude Monet (1840-1926) would leave behind some 200 paintings of the waterlily pond he had built at his home in Giverny, which were painted from about 1899 to the year of the artist’s death. These works were unique in that Monet composed them solely of an expanse of water, as if cut out of the pond’s surface, with no horizon or waterline and no sky— elements normally considered essential parts of a landscape painting. In this painting of the pond surface dotted with waterlilies, the branches of the weeping willows and poplars that line the banks of the pond are reflected in deep green running down the right and left sides of the canvas, while the sky is reflected as a light green expanse in the center. It is a mysterious world in which waterlilies floating on the pond and the trees and skies reflected on the pond’s surface exist together and reality intersects with illusion, all within the quintessential flatness of the water surface. In the year Monet painted this painting, he also worked on about 15 paintings of similar composition in vertical format and canvas size. From the difference in the colors used in these works, we see Monet’s signature method of painting the same scene in different lights at different times of day.

This colorless gray picture plane is defined by rounded curving lines and geometrically drawn straight lines that form an interesting composition with the appearance of something assembled from nondescript found objects such as wood fragments from the sea floor or stones. However, what the artist Picasso (1881-1973) depicts here is actually the figure of a sleeping woman. The circle in the center is a mouth lined with teeth and the surrounding oddly shaped, mushroom-like forms are the head and neck, while the two crescent shaped lines represent closed eyelids. Lying below the long neck is a luxuriant swell of breast. Although each part may appear flat in itself, the way they overlap creates a sense of depth. During the spring of 1927, Picasso did at least five paintings of sleeping women with open mouths. In the unconsciously opened mouth is a full line of teeth, perhaps suggesting an unexpected beastly side to the voluptuously bodied woman.

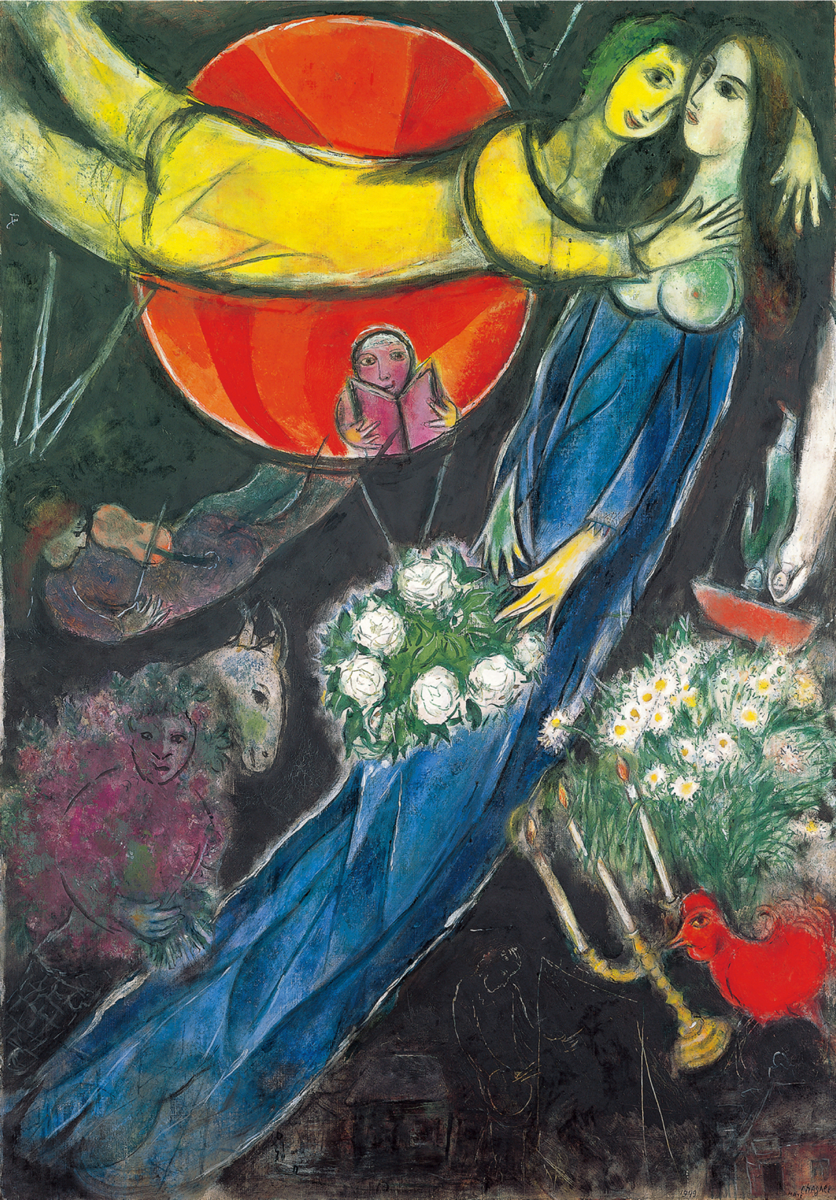

The Red Sun, 1949, 139.5 × 98.0cm

© ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2024 G3689

Among the group of foreign artists active in Paris in the first half of the 20th century known as the “École de Paris,” Marc Chagall (1887-1985) is especially well known. As a Russian Jew, however, he had no choice but to flee from France during the Nazi invasion and decided to go to the U.S. The work The Red Sun was painted by Chagall shortly after returning to France after the War. In it we see Chagall’ s mysterious world in which figures float in the air as if weightless. The bright colors of the figures, animals and bouquets against the nocturnal darkness of the background seems to reflect the artist’s desire to hasten the recovery from the dark war era. We see a line drawing to the lower left of the candlestick made by etching in the black paint with a sharp instrument. What is drawn there is none other than the Chagall of his younger days painting at his easel.

The Birth and Development of Abstract Art

Gallery 103 ─ Early Abstration

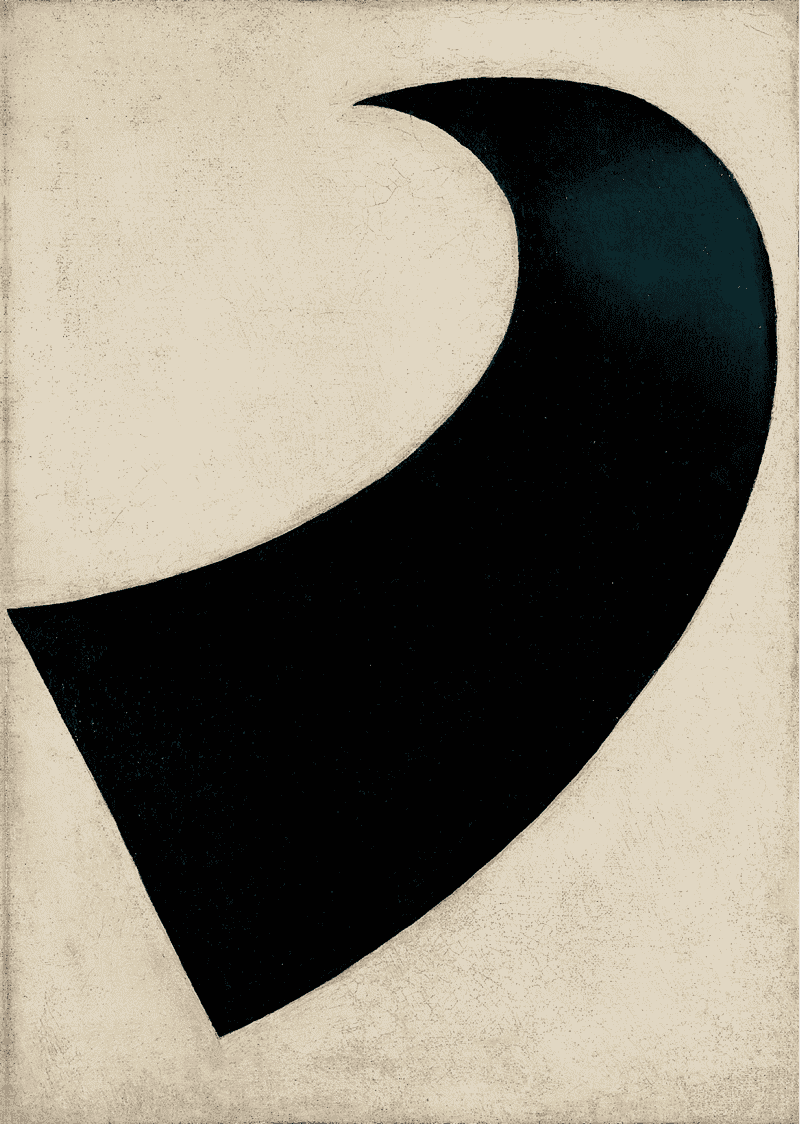

As one of the representative artists of the Russian avant-garde, Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) showed 40 paintings in the “Last Futurist Exhibition of Pictures:0-10” in St. Petersburg in 1915. These paintings consisted of geometric forms including rectangles, circles and crosses painted in black on white canvases in a style that Malevich called “Suprematism.” Completely negating the depiction of objects and phenomenon of the natural world visible to the eye, Malevich and his disciples put forth a theory of painting that dealt with non-visual abstract subjects such as mass, movement and the energy and forces of the universe. This Suprematist movement became very influential in Russia following the 1917 revolution. The work Suprematism in the collection of the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art was painted in the year of the Russian Revolution. It has a simple and dynamic composition with a vanishing point at the top of the painting and marvelous overall balance that continues to exert its mysterious appeal on viewers to this day. With the rise to power of Joseph Stalin, Suprematism would soon come under criticism from Russia’s Communist Party, resulting in an abrupt end to the movement. However, Malevich’s abstract painting theory would continue to have a strong influence of 20th-century art.

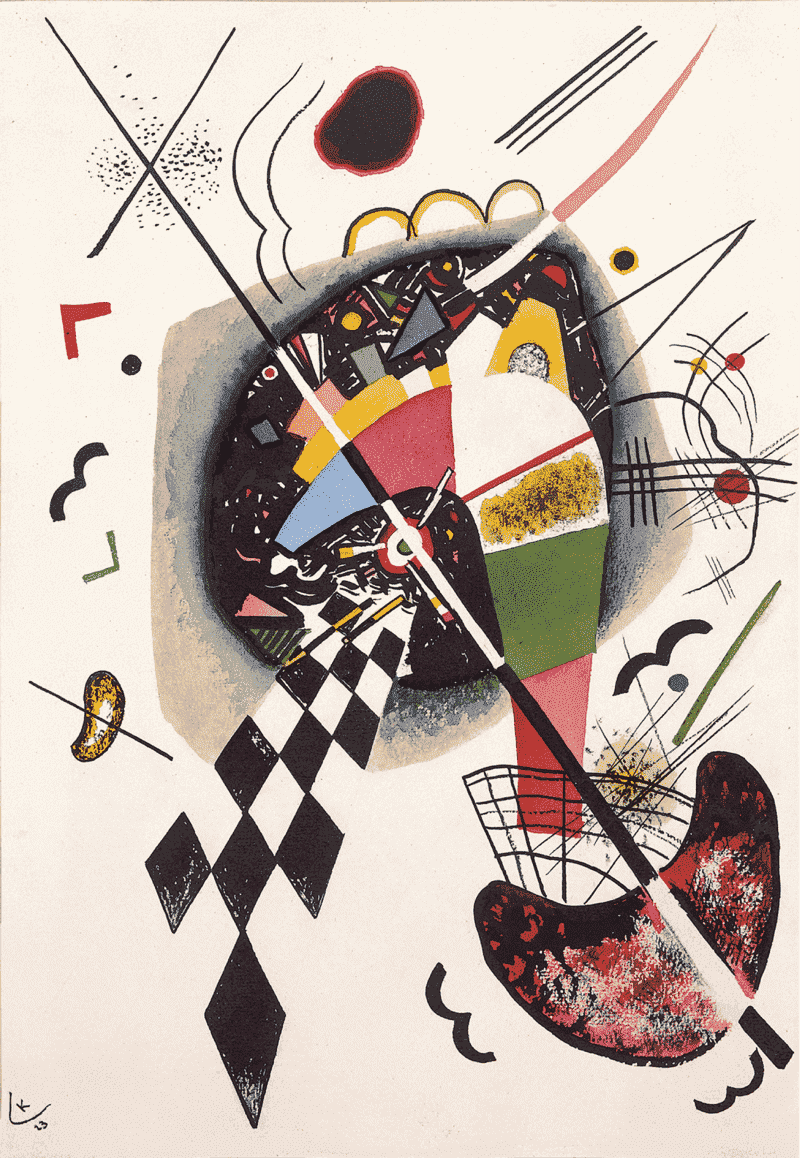

The Russian-born artist Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) was one of the important originators of abstract painting, or non-objective painting, the type of painting that depicted subjects in colors and shapes unrelated to any actual objects. Also an excellent violinist, Kandinsky came to think that, just as music used combinations of rhythm and tone to create emotive atmospheres that move the listener, so too could combinations of color, shape and the like be used purely as creative elements to compose unique worlds independent of known reality. This painting, with its rhythmical composition of forms of varying colors, sizes and shapes on a white background, has a lively atmosphere suggestive of improvisational jazz. The process through which the artist arrived at such a composition of colors and forms involved repeated studies on narrative subjects, through which the forms gradually became simplified. The boomerang shape at the center and the many-colored shapes arranged above it derive from the fortress-on-a-hill image that Kandinsky painted numerous times in 1910 along with a scene seemingly depicting the Old Testament story of Noah and the Deluge. Also, the reddish black crescent moon shape in the lower right corner and the mottled black and white diagonal line that rises from there to the left are motifs originating from paintings the artist did on the theme of St. George spearing the mouth of the dragon with a long lance, also from the year 1910. It may be that painting subjects like the terminal Deluge and knights slaying dragons were an inspiration to Kandinsky in his ongoing quest to establish abstract painting.

1943, 127.5 × 102.0cm

Among the artists creating abstract art after World War I, László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) was particularly interested in scientific and technological advancement and believed that they could help open up a brighter new world. Throughout his life as an artist, Moholy-Nagy created works involving the element of light. Some examples were the new photographic method called “photograms,” such creations as sculptures made with transparent plastic and motorized 3-dimensional works made of metal and glass. In 1940, Moholy-Nagy created a relief titled Space Modulator (Plexiglass) that was very similar in composition to this work in the Kawamura collection. It was different from any form of painting until then. It had a two-layer construction with a transparent Plexiglass plate engraved with lines and colors placed in parallel in front of another plate of uncolored plastic to catch the reflections of light projected on the pair of plates from various directions. The name “Space Modulator” was intended to describe the way light and movement could be modulated to create new spaces. We can assume that the work Space Modulator CH 1 is an oil painting depicting an image and the accompanying light phenomena created by Space Modulator (Plexiglass). Given the poor durability of the plastic used in Space Modulator (Plexiglass), the artist may have felt the necessity to create a more permanent image using oil paint.

From Dada and Surrealism

Gallery 104 ─ Surrealism Art Movement

1932, 10.0 × 22.0 × 22.0cm

© VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2024 G3689

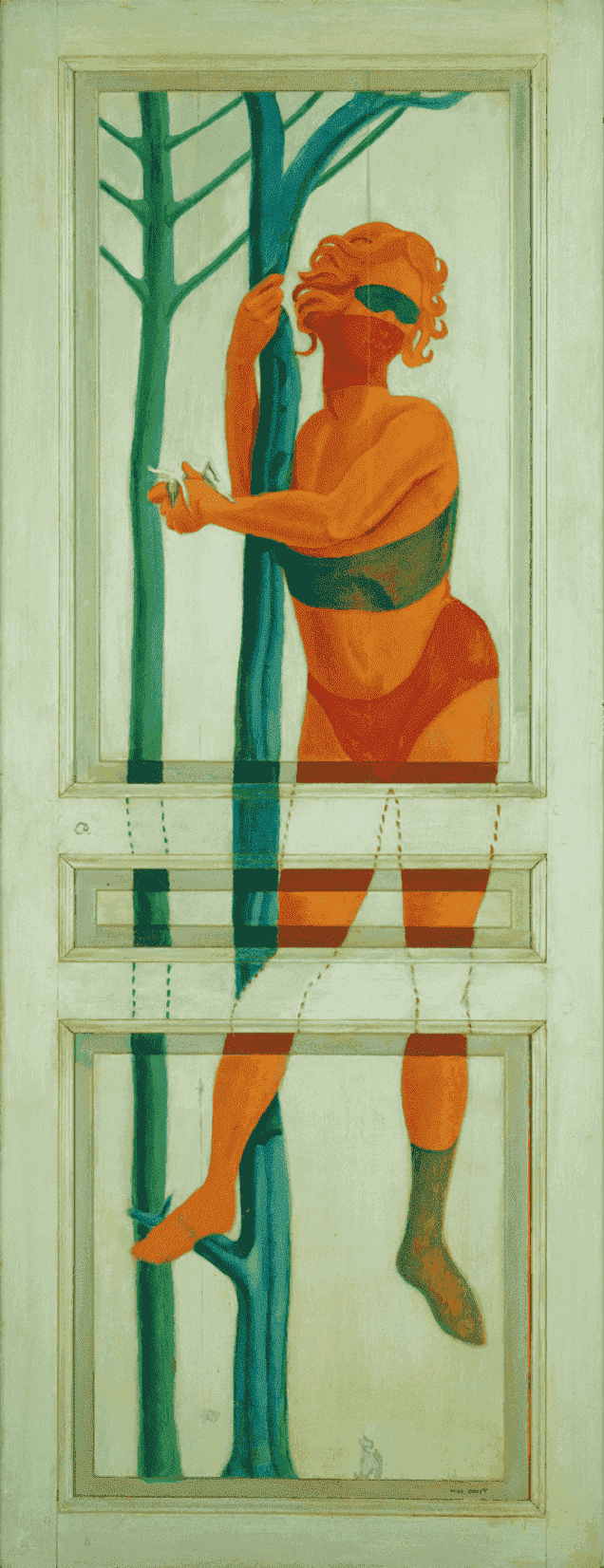

1923, 205.0 × 80.0cm

© ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2024 G3689

As World War I enveloped all of Europe, people succumbed to feelings of hopelessness and despair. It was this atmosphere that gave birth to Dadaism, as conventional values crumbled and artists adopted the “meaningless” and the “haphazard” as elements of expression in literature and art. The result was a movement that breathed fresh new spirit into the European society. Jean Arp (1886-1966) was a participant in this movement, and after moving to Paris he also took part in the Surrealist movement. He created collage works with compositions employing natural happenstance, such as the patterns created when scraps of paper he tossed in the air landed on the floor or table. Later, in the 1930s, Arp focused on the creation of bronze sculptures with natural organic forms.

In the work Two Thoughts on a Navel in the Kawamura collection, slug-like objects depicted as “thoughts” seem to be crawling over a donut-shaped form that can be seen as a human navel. With the combination of a part of the human body and one of the lower forms of animal life in this humorous work, Arp is apparently poking fun at the concept of human supremacy and expressing a concept that places the human being on parallel with the creatures of nature and the universe.

It wasn’t long before two of the central figures of the Dadaist movement in Paris, the poets André Breton and Paul Éluard,soon began to recognize the limitations of this movement and separated themselves from it completely. As its alternative, they began the Surrealist movement, which rejected the rationalism of modern society and used methods similar to psychological tests such as oral experiments during sleep and automatism in pursuit of artistic expression that deeply involved the subconscious.

Max Ernst (1891-1976) was one of the representative painters of the Surrealist movement, and he employed new methods including frottage and decalcomania to express a metaphysical world. After his talent was recognized by Éluard and his wife Gala, Ernst took up residence at the Éluard home. During his stay there, Ernst executed paintings on the walls and doors of numerous rooms of the house. However, after the Éluard family sold the house, the new residents removed the strangely painted doors and painted or wallpapered over the paintings Ernst had created on the walls. These lost works were eventually forgotten, until the year 1967 when Éluard’s daughter, Cécile recalled them from her youth and retrieved what she could of them from under layers of wallpaper or from the storeroom where they had rested for years. One of the recovered paintings is the work Entrer, Sortir in the Kawamura collection, which was originally painted on the dining room door of the Éluard home. The model in the painting is believed to be Gala, who eventually became Ernst’s lover.

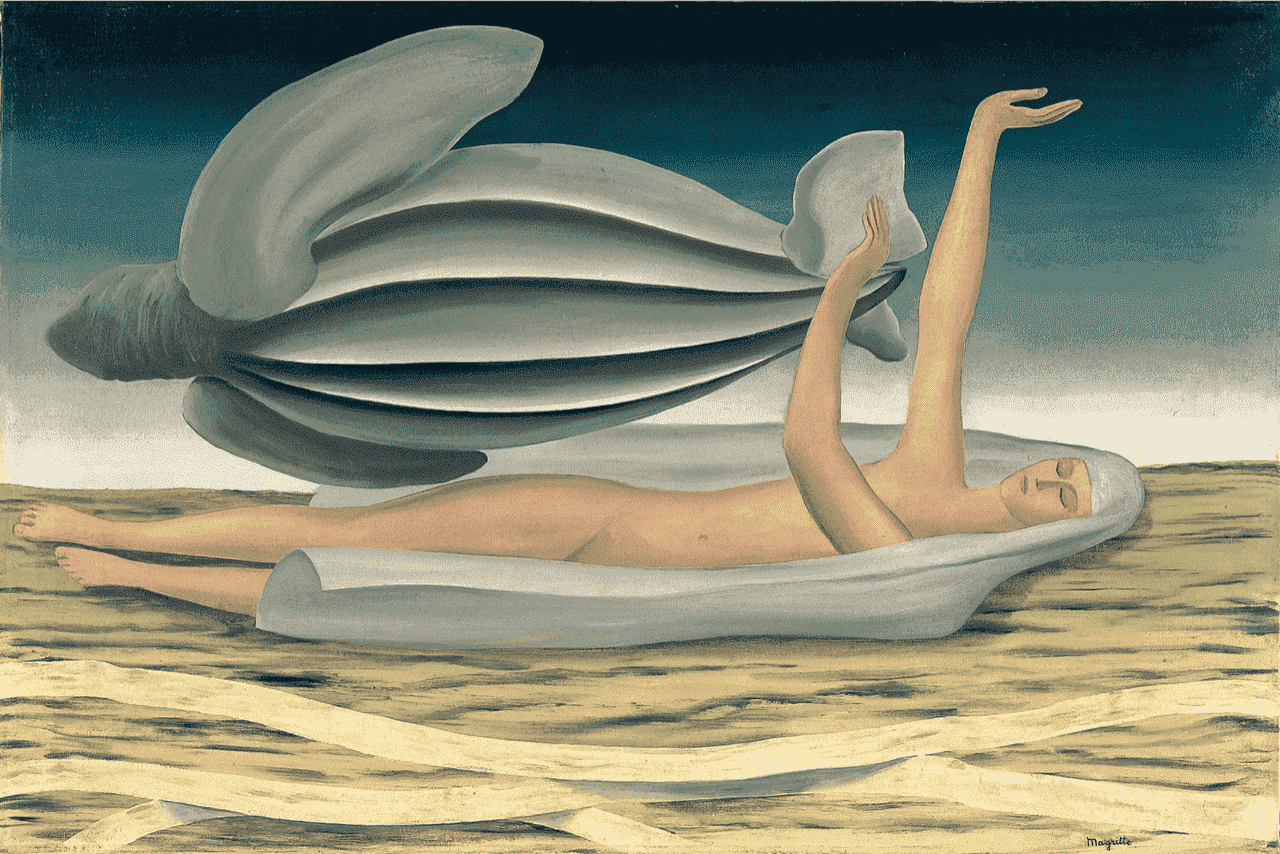

© ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2024 G3689

A representative Belgian painter of the 20th century, René Magritte (1898 – 1967) also had a distinct presence within the Surrealist group and was a close acquaintance of Éluard as well as Miró and Arp. This work, The Garment of Adventure from 1926, is one of the early works of the artist’s career. A sea turtle with an appearance like that of a blimp floating in the air is said to have been taken from an illustration in France’s Larousse Encyclopedia. The link between the lying figure in a veil with arms upstreched and Magritte’s mother who drowned herself when he was 14 has been pointed out. However, there is also something humurous in the juxtaposition of the figure with its strong association with death and the calm composure of the sea turtle. In this way, the unexpected combination of these elements seems to create a dreamlike atmosphere that draws us into a mysterious world. Magritte employed various techniques to bring mysterious images into his paintings with the use of things like combinations of elements or distortions of objects that could never occur normally in the real world and the eccentric nature of his titles related to the subjects depicted. Magritte said that mystery was absolutely essential for reality to exist, and without it, no thought or worlds could exist. And the painting that he envisioned was a process of making thoughts visible in order to summon up that mystery.

Joseph Cornell: Seven Boxes

Gallery 104 ─ Joseph Cornell

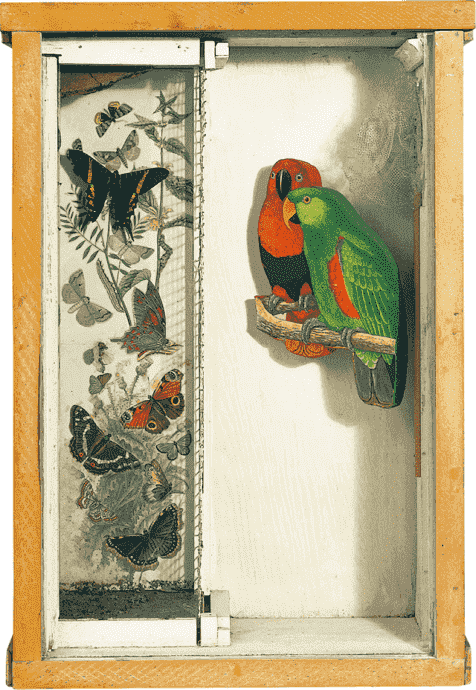

© The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation /VAGA at ARS, NY/ JASPAR, Tokyo 2024 G3689

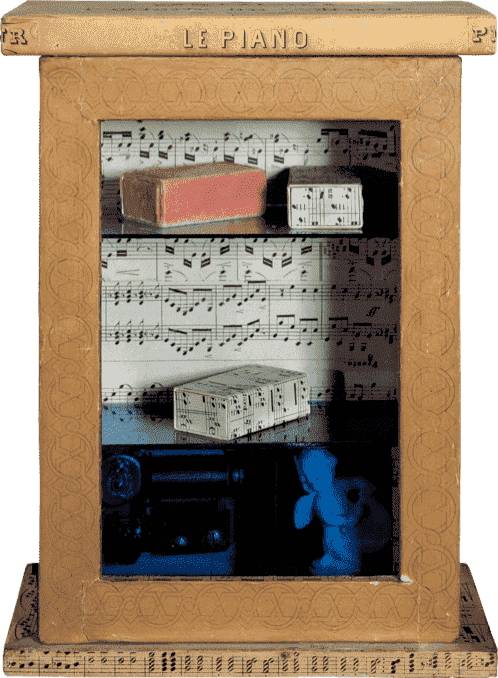

© The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation /VAGA at ARS, NY/ JASPAR, Tokyo 2024 G3689

© The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation /VAGA at ARS, NY/ JASPAR, Tokyo 2024 G3689

The American artist Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) is known as the “box artist.” In 1931 he became inspired by the Surrealist art of Ernst, Dali and others and soon began creating collage works of his own, before switching to the box compositions that he would continue creating for the rest of his life. In these works he made boxes of about the size that could be held easily in both arms and filled them with a variety of objects that he fancied. For Cornell these were both “treasure boxes” and showcases in which he could display his own unique worldview.

In the work Untitled (Parrot and Butterfly Habitat), butterfly and moth specimens that he found in specialty shops play together with others cut out of bug encyclopedias, while beside them parrots look on. This little world has the orderliness of a museum display case. Seen from another perspective, however, the parrots and butterflies that inhabit this box, with its metal divider and a butterfly net hung on the wall, may also be manifestations of Cornell’s longing for exotic worlds he would never see. Forced to go to work at a young age to support his mother and younger brothers, Cornell would never set foot out of his native New York.

In Untitled (Le Piano), a slightly smaller box is lined throughout with sheet music, creating a work that shows Cornell’s love of music. From the music scores that he probably bought at the used book stores of Manhattan he chose a piano adaptation of a 19th century European romantic opera, and if you follow the notes you can perhaps hear the elegant intonations of its music. What’s more, this work is also designed to actually provide music for the ears as well. Inside the lower half of the box enclosed behind blue glass is a music box that plays Mozart’s Piano Sonata in C Major (K. 545) when you wind the key at the back of the box.

The things Cornell put in his boxes are not only collector’s items like bug specimens and rare musical scores but also everyday items like cork balls and cordial glasses of the kind sold at the local variety store. When placed in his boxes, these items took on symbolic meanings beyond their inherent utilitarian significance. For example, the white cork balls set to roll on the two metal rods in Celestial Navigation by Birds, can not only be seen simply as toys but also as symbolic images, such as celestial bodies revolving in the heavens or innocent-spirited migratory birds in flight. Also, if you see the blue of the box interior as the blue of the sea instead of a blue sky, we can imagine the ceramic pipe, the shells and the broken piece of board with bent nails in it to be the remains of a wrecked ship that sunk to the sea floor long ago. And it is surely because these works are in the microcosm of a box that we feel this kind of expansiveness over time and space.

Mark Rothkoʼs “Seagram Murals”

Gallery 106 ─ Mark Rothko Seagram Murals

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / ARS, New York / JASPAR, Tokyo G3689

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / ARS, New York / JASPAR, Tokyo G3689

The seven paintings of Mark Rothko’s “Seagram Murals” series in the collection of the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art are works that were originally intended to hang in the same room. Rothko (1903-1970) created the Seagram series as a result of a commission that came to the artist in the spring of 1958. Having become a painter of renown around the middle of the 1950s, he was asked to create paintings to decorate one room of what was to be an exclusive restaurant named The Four Seasons in Manhattan’s Seagram Building. The restaurant was to offer the very finest cuisine and outstanding art, and Rothko was chosen as one of the artists to provide that art to decorate it. At the time, Rothko had come to dislike having other artists’ works hung in the same room with his in group exhibitions, preferring to create an artistic space by filling one room with his own works exclusively. That would be the case with The Four Seasons commission, and Rothko spent about a year and a half creating 30 paintings for the project.

These “Seagram Murals” are different in a number of ways from other representative paintings of Rothko that release a light quietly from within a cloud-like expanse of color. First of all, the majority of them are horizontal works and larger that earlier Rothko paintings, with many reaching 4.5m in width. The reason they are so much larger than his earlier works is that Rothko thought of them as murals, not paintings, and from sketches he left on paper it is clear that he intended to hang several of them in sequence with no space in between, thus literally covering an entire wall in mural fashion. Also, they no longer have the cloud-like color field of his previous paintings. Instead, each painting has a deep reddish brown base color over which is painted a window frame-like form in red or black or a light orange. That said, it is not a literal window frame but the concept of a “window” that is represented—a window to a red expanse of the world beyond, perhaps a door. And whichever, it is closed, it only represents a boundary between this world and the world beyond and it defies any desire we might have to cross over into that world. Some people might feel averse to the color, finding it suggestive of dried blood, or the unique texture of his finely layered paint. But if you sit for a while surrounded by these murals, you may find yourself feeling as if your consciousness itself has been dyed the same red and your thoughts turned toward deep introspection.

In an ironic twist, these Seagram Murals that opened up a new realm of Rothko’s art would never be hung in The Four Seasons restaurant after their completion. Rothko was disappointed with the atmosphere of the restaurant when he visited it for the first time after its opening and ended up breaking his commission contract. Although the murals were thus denied their intended home, nine would be donated to The Tate Gallery (now the Tate Modern in London) in 1970 and seven would eventually come to the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art in 1990. These museums have since constructed rooms specifically for the permanent display of their Seagram Murals. Besides these, collections of Rothko can be seen as originally intended in rooms of their own in the U.S. in The Rothko Room of The Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. and The Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas.

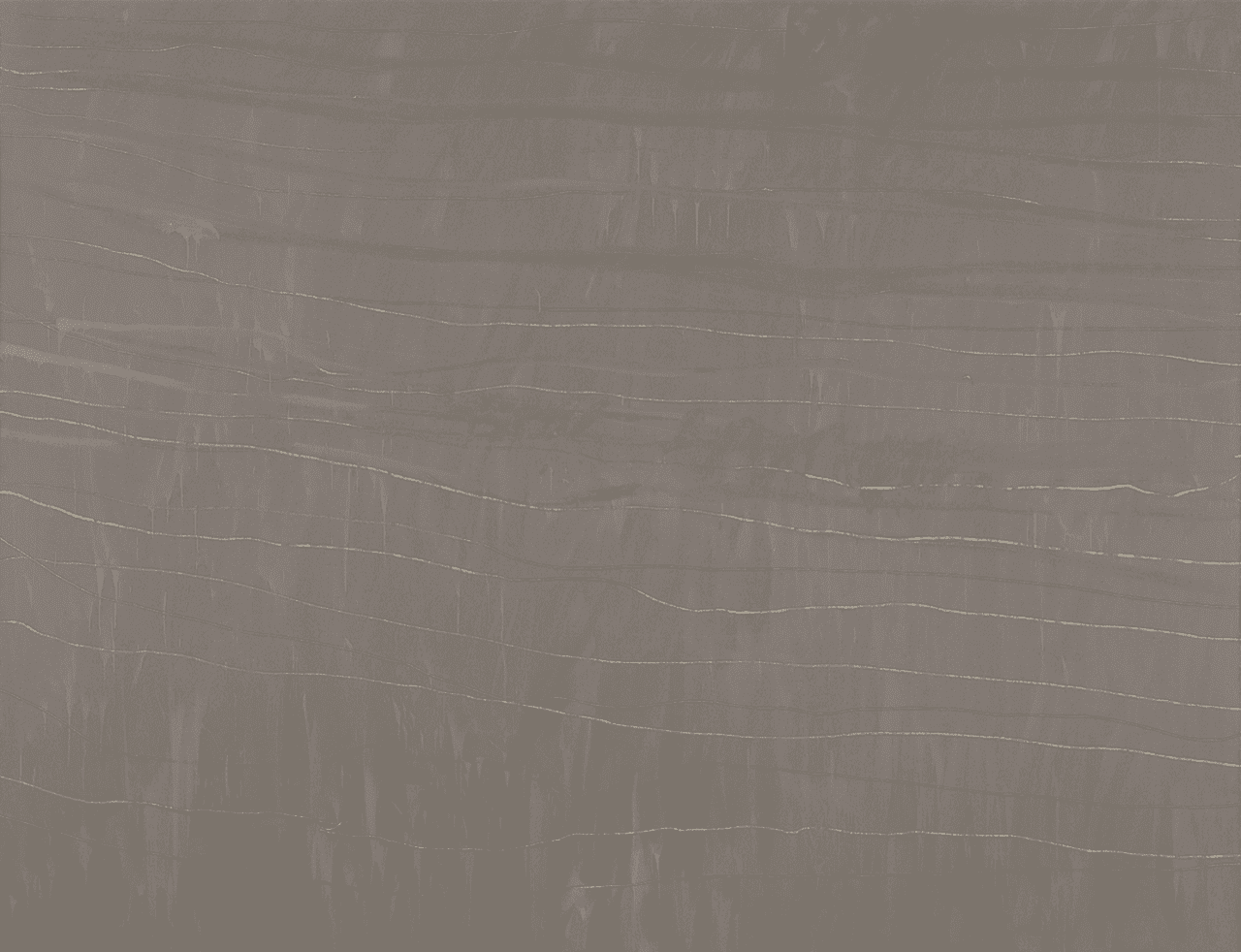

The Painting and Sculpture of Cy Twombly

Gallery 200 ─ Cy Twombly

© Cy Twombly Foundation

Cy Twombly (1928-2011) was a leading painter and sculptor of the generation that followed the masters of Abstract Expressionism such as Rothko and Pollock, and as an artist he was one of the most original of the 20th century.

Twombly’s art is best known for drawings in which his lines weave freely across the picture plane with traces of awkwardness remaining here and there. It is a technique that developed from the practice of letting the pencil in his hand move freely across the paper in the dark so that the lines represented nothing but the movement of the hand, unfettered by the eye or thoughts in the mind. In these lines that are not drawn to depict something but allowed to play freely as if of their own will, we find the innocence of a child’s scribbling as well as a feeling of vital life force. The 1968 work Untitled was executed by covering a canvas with a thin coat of grey house paint and then, before it is completely dry, drawing a series of lines in white crayon and chalk from the left- to the right-hand side of the canvas. From the lines, which are at times etched with strength and other times in delicate line and also at varying speeds, we feel a flow, like that of a great river or the wind. We can see places where the lines have been painted over and new lines drawn on top, but since the original lines are never completely painted out, we see traces of them beneath the paint and lines layered on top and this gives depth to the work, as if a sense of time eternal is captured within.

©Cy Twombly Foundation 2018

Although the works are fewer than his drawings and paintings, Twombly also did excellent work in sculpture. His first works of sculpture date to 1946 and by the early 1950s he had already developed a unique style of sculpture works assembled from things like cloth, scraps of wood and parts of daily commodities and then painting the construction white. After the 1960s, when Twombly left sculpture to concentrate on his painting, he began to work ambitiously on sculpture again from 1976 and actively displayed his work. It can be said that the artist achieved in his sculptures an appeal similar to the gentle, free-flowing atmosphere of his line drawings by means of the fragile materials he chose and loosely connected together into forms defined by their fine balance. This sculpture Untitled (1990) is the first of an edition of five cast [bronze] sculptures based on the plaster sculpture Twombly exhibited at the 1988 Venice Biennale (a work that connected a plaster form to two standing wooden poles).

©Cy Twombly Foundation 2018

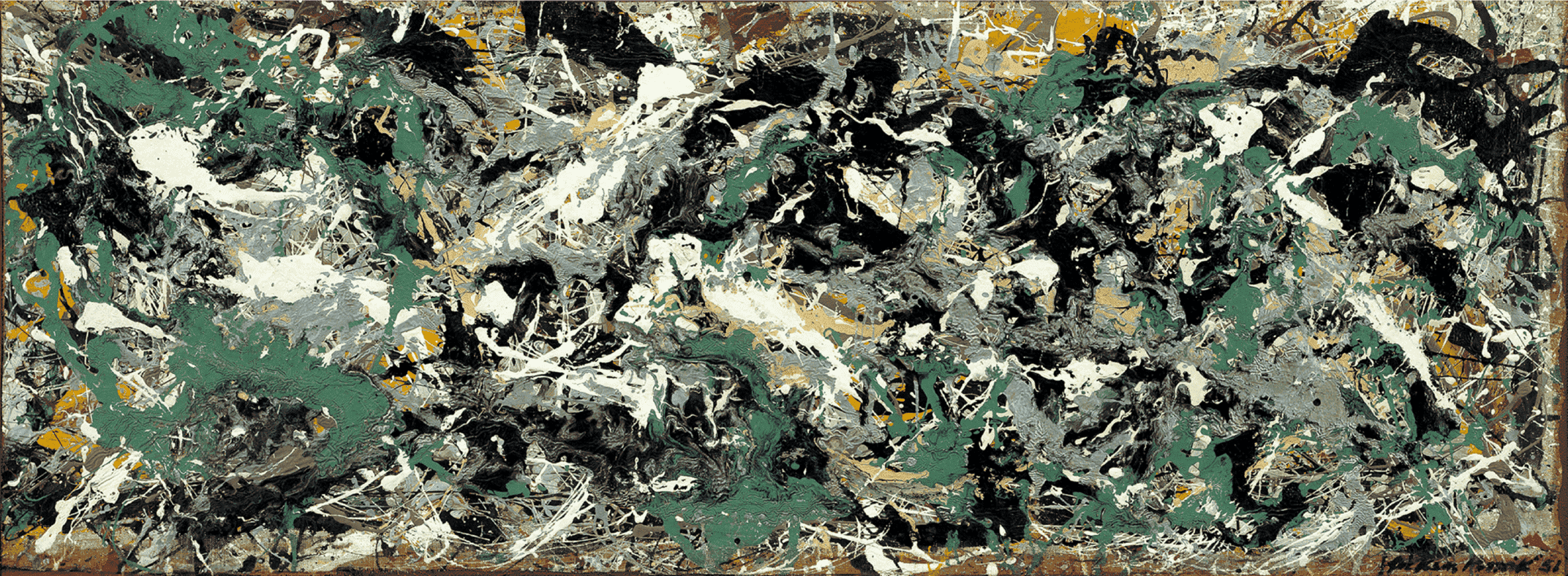

From Abstract Expressionism to Minimalism

Gallery 201 ─ American abstract paintings

World WarⅠprompted the emergence of a number of new art movements in Europe. During World War Ⅱ, however, many of the artists involved in those movements moved their base of activities to the U.S. to avoid the ravages of war. These European artists actively interacted with the young generation of American artists, who were thus able to absorb the latest trends in European avant-garde art. After the War, the gravitational center of the art world had effectively shifted from Europe to America. Here, a new type of abstract painting was born, one in which large canvases well over the height of an adult were covered with fields of color. On their huge canvases, the American artists created works that reflected the fundamental themes of art such as tragedy and the sublime in human nature, creating a new field of art that came to be known as Abstract Expressionism. Among the leaders of this new movement, along with Mark Rothko was Jackson Pollock (1912-1956). The Pollock work Composition on Green, Black and Tan is painted in the artist’s signature style with white, black, green, tan and silver paint dripped and splattered across the canvas, creating a seemingly infinite number of intersecting lines. Although lines are the central element in Pollock’s paintings, the lines do not depict any specific forms. Neither are these paintings abstract representations of any things existing in the physical world. Pollock’s works were a rejection of the conventional structure of painting until that time and became symbols of the new art emerging in America.

Ad Reinhardt (1913-1967) is an artist of the same generation as Pollock. In 1960, Reinhardt painted black paintings on 1.5 meter square canvases, dividing the canvas into thirds vertically and horizontally and painting in the spaces with three shades of black that can barely be differentiated. After that he continued to paint this type of extremely pure and simple painting executed only in black on square canvases until his death, using the same size, the same composition and the same blacks.

The work Abstract Painting in the Kawamura collection is one of these paintings, and in its simple form and extremely restricted creative method we can see Reinhardt’s sincere approach to the question that occupied the minds of artists at the time, what a painting is. His approach of stripping down the elements of a work to the absolute minimum became seen as a method that sparked the later trend that came to be known as Minimalism.

Entering the 1960s, a new group of artists emerged who objected to abstract painting and favored painting that took actual figurative images as subjects. As the standard-bearer of the Pop Art movement, Andy Warhol (1928-1987) created screenprint works composed of sequences of images of the type that flooded the mass media, such as the face of Marilyn Monroe and commercial goods like Coca Cola and Campbell’s soup. These works instantly made him the darling of the New York art scene.

Of all the artists who have ever taken flowers as a subject for painting, Warhol was surely the first in the history of art to take as his motif “just a flower,” simple flowers unrelated to any proper noun that would distinguish them from others. His creative process was bold and decidedly indiscrete; he simply took an image of a hibiscus flower he happened to see in a magazine and, without permission, enlarged it and transferred it to silkscreen to produce prints.

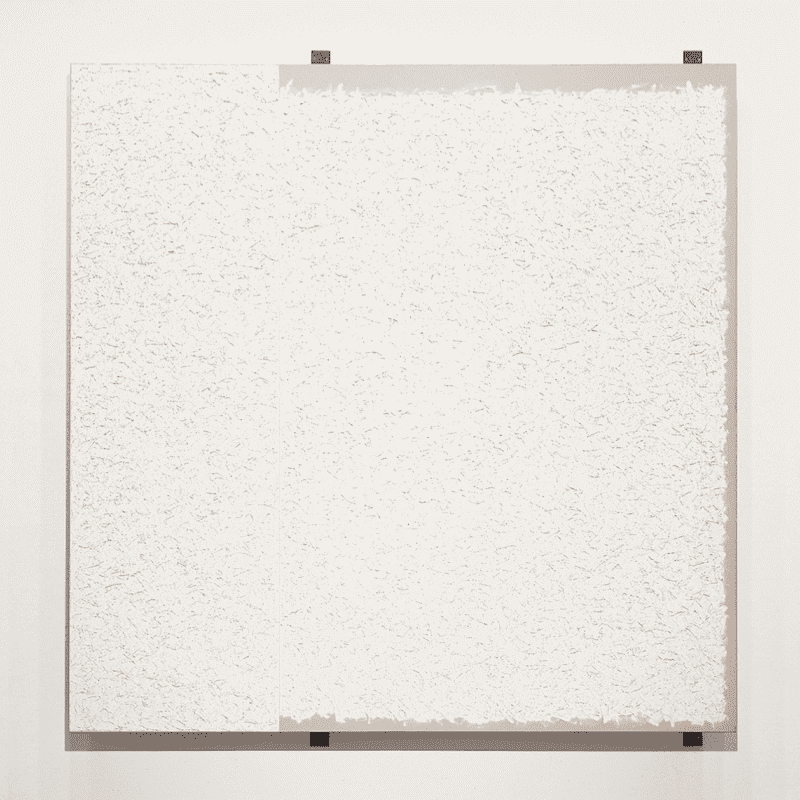

In virtually the same period as Pop Art, a category of works that would come to be called Minimal Art was also appearing. It was art that striped away the subjective or emotional expression of the preceding Abstract Expressionists’ art and sought to pursue the fundamental questions of artistic creation using clear and simple forms. Robert Ryman (1930-2019) emerged in the late 1950s as an artist who created simple abstract paintings using mostly white paint applied to square canvases. Through variations in size and material, types of paint and the way it was applied to the canvas, he strove to disclose the essence of composition and construction in painting and thus reveal the expressive qualities unique to painting.

© ️2024 Robert Ryman / ARS, New York / JASPAR, Toky G3689

In this painting titled Assistant, the left side of the canvas is covered completely in white paint, while empty spaces are left that reveal the canvas surface. The metal fasteners that normally are used on the back of the canvas unseen are attached in a way that they are visible and thus show the inherent physical nature of painting’s construction. Things like the slight contours in the paint left by the brushwork and the resulting shading it creates serve to open the viewers’ eyes to detailed variations in the painted surface that normally remain unnoticed.

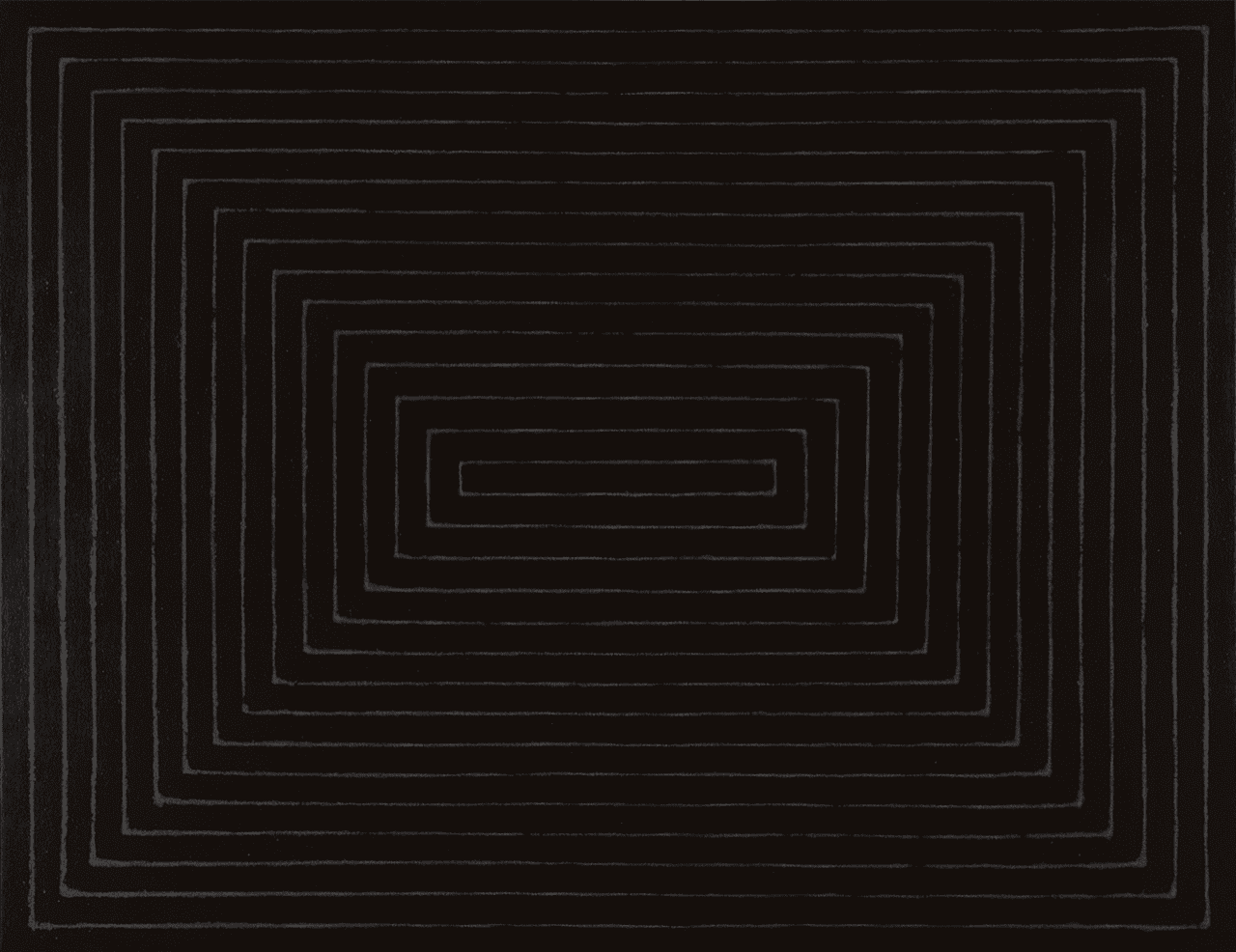

Frank Stella’s Artistic Quest

Gallery 201 ─ Frank Stella

Frank Stella (1936-2024) is an artist who continued to overturn the artistic conventions of the day with bold new concepts, while progressing in style throughout his career by experimenting with new types pictorial spaces. The extensive collection of Stella works in the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art is one of the museum’s widely recognized strengths, as well as being one of its visual highlights.

© ️2024 Frank Stella / ARS, New York / JASPAR, Tokyo G3689

Born in Malden, Massachusetts in the USA, Stella studied art history at Princeton University. After graduating and moving to New York the following year to begin his pursuit of art, Stella created a series of works that came to be known as his ‘black paintings’, among which was the work Tomlinson Court Park (second version). Using commercial enamel paints and flat brushes, he created paintings consisting purely of repeated patterns of stripes on large canvases. The abstract paintings of this period, in which Stella reduced the compositional elements to a minimum, represent one of the earliest forms of what would come to be known as Minimalist Art. What are we the viewers to find these reticent paintings executed in a single black that resists our efforts at interpretation and gives an impression of inscrutability? Stella’s own suggestion to people who would wonder what they should find in his paintings is, “What you see is what you see.” In these words the artist is saying that the way to look at these paintings is to dispense with our habit of looking beyond the surface—as we do with TV or computer screens—for virtual realities that do not actually exist therein and, instead, to accept the painting simply for what it is and what we see in front of us.

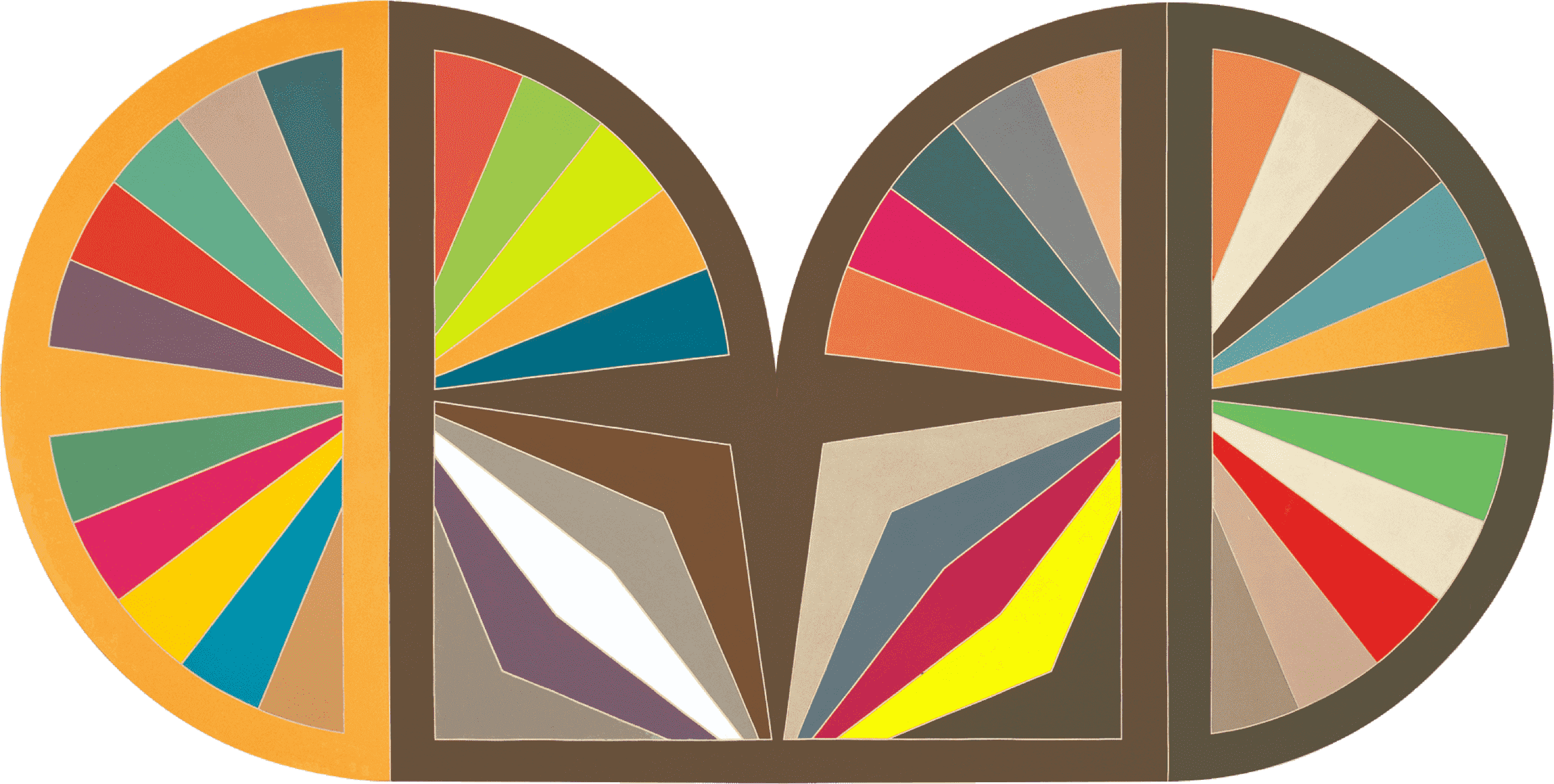

© ️2024 Frank Stella / ARS, New York / JASPAR, Tokyo G3689

The year after Stella painted his Tomlinson Court Park paintings, he abandoned the long-held painting convention of working on rectangular canvases. The painting Hiraqla Ⅲ executed on a canvas shape resembling a pair of glasses is from Stella’s “Protractor Series” composed of semicircular units. Indeed, the radiating color sections of the semicircular forms are as if drawn according to the angle calibrations of a protractor. The shapes are the product of Stella’s attempt to achieve a complete unify between the image he wanted to paint and the shape of the canvas he painted it on. As such, his method was a complete reversal of the conventional process of beginning with the predetermined picture plane of a rectangular canvas and then painting an image within it. This is an expression of Stella’s belief that a painting is not a screen to reflect things but a physical object and entity in its own right. Meanwhile, unlike the monochrome Tomlinson Court Park, the multicolor composition including fluorescent colors the artist employs in Hiraqla Ⅲ creates a pictorial space of vibrant dynamism that defies the limits of the two-dimensional canvas.

1972, 275.0 × 257.5 × 23.0cm

© ️2024 Frank Stella / ARS, New York / JASPAR, Tokyo G3689

The next big development that occurred in Stella’s work was that, in addition to the change in external configuration of his canvases, he overturned the conventions of painting once again by adopting new materials for his supports in what was titled the “Polish Village Series.” In this series including the work Bechhofen Ⅲ, he replaced the fabric-covered canvas with packing and building materials like thick but light Tri-Wall cardboard. These materials were then cut into component parts and assembled as the support, and on some parts Stella would apply a surface layer of paper or felt. Each of the parts making up these compositions would be of different thicknesses and positioned at angles in relation to the wall’s horizontal. The effect of these complexly constructed compositions of this series gave the works a stronger architectural aspect compared to the artist’s previous work. In fact, the inspiration for this series was a book given to Stella by old friend and architect Richard Meier, titled Wooden Synagogues.

© ️2024 Frank Stella / ARS, New York / JASPAR, Tokyo G3689

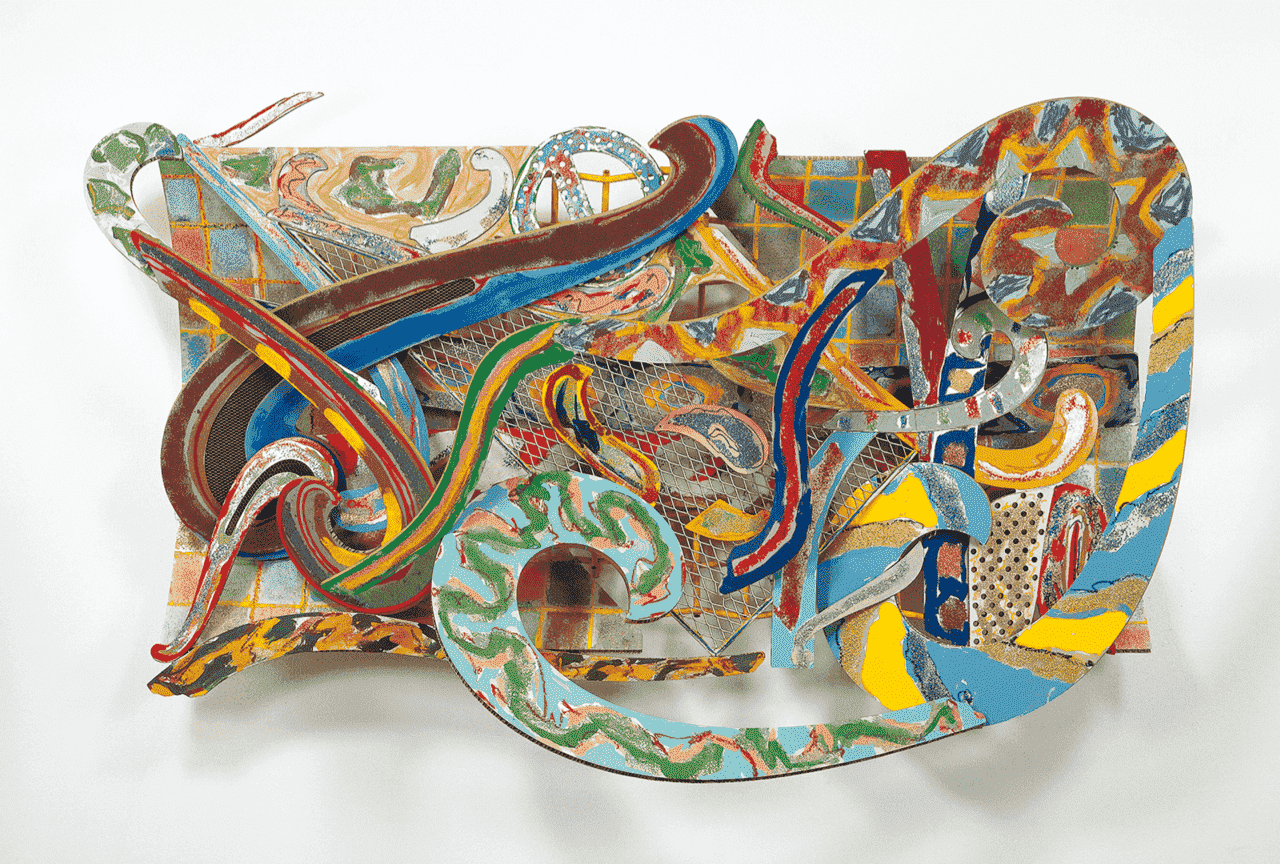

As Stella’s artistic quest continued, from 1975 he used sheet aluminum in works assembled from numerous parts in increasingly 3-dimensional form.

Among these were works that tempted us to ask if they were indeed paintings, but Stella insisted that if it was a work to be hung on a wall, they were ‘paintings’, no matter what form they took. One of these works, whose title was taken from a book of birds Stella acquired while visiting India, Shāma, 5.5X, consisted of some 20 parts attached in a complex array to a grid constructed of pipe. With some parts protruding out nearly 90 cm, that created the effect of a ‘painting jumping out from the wall’. Taking a lesson from the problem of weight in the “Polish Village Series,” this work used light honeycomb aluminum sheets, which enabled the attachment of such a large number of parts. Some these parts were brightly colored and stretched across the composition with curving lines and curled ends in the shape of French curves. Like his stripes, this was a motif that Stella fell in love with at first sight. Surely, the movement of these curved parts painted with bright colors and rough brushstrokes, and the sparkle of metallic parts scattered around the composition, awaken in us an image of colorful tropical birds flying freely.

Japanese Contemporary Art

Contemporary art in Japan

In the contemporary era, Japanese artists have continued to pursue their own unique modes of expression, in parallel with but distinct from the art movements that have emerged internationally. In discarding the old artistic conventions that had lost their luster in the changing times, these artists have been involved in a process of exploring anew what art is and also what the human being is in the contemporary world.

Natsuyuki Nakanishi (1935 – 2016) was a painter who pursued his art with a unique theory of what constitutes painting. In his solo exhibition QUARTET-Touching Down on Land and Touching Down on Water X, at our museum in 2004, in which Nakanishi created a large installation using materials like a semi-transparent curtain and metal sand. For the artist, this creation could be said to create a special place as painting or a model for painting. The Four Beginnings series that Nakanishi began in 1999 was followed by the R・R・W-Four Beginnings series of works that continued until 2002. The Kawamura Museum has one work from each of these series in its collection. In the series of drawings related to these works, we see a process in which the artist’s pen moves around the picture plane and in a way that results in points of intersection, the lines of which the artist then proceeds to surround with green paint to create four circles, while a grid of lines and “X” marks at points around the canvas and color surfaces of white, green, orange and purple interact with each other to create a shimmering effect. More than posing a question of what the artist is depicting, the resulting work offers us an experience of exploring the special physical entity that is a painting.

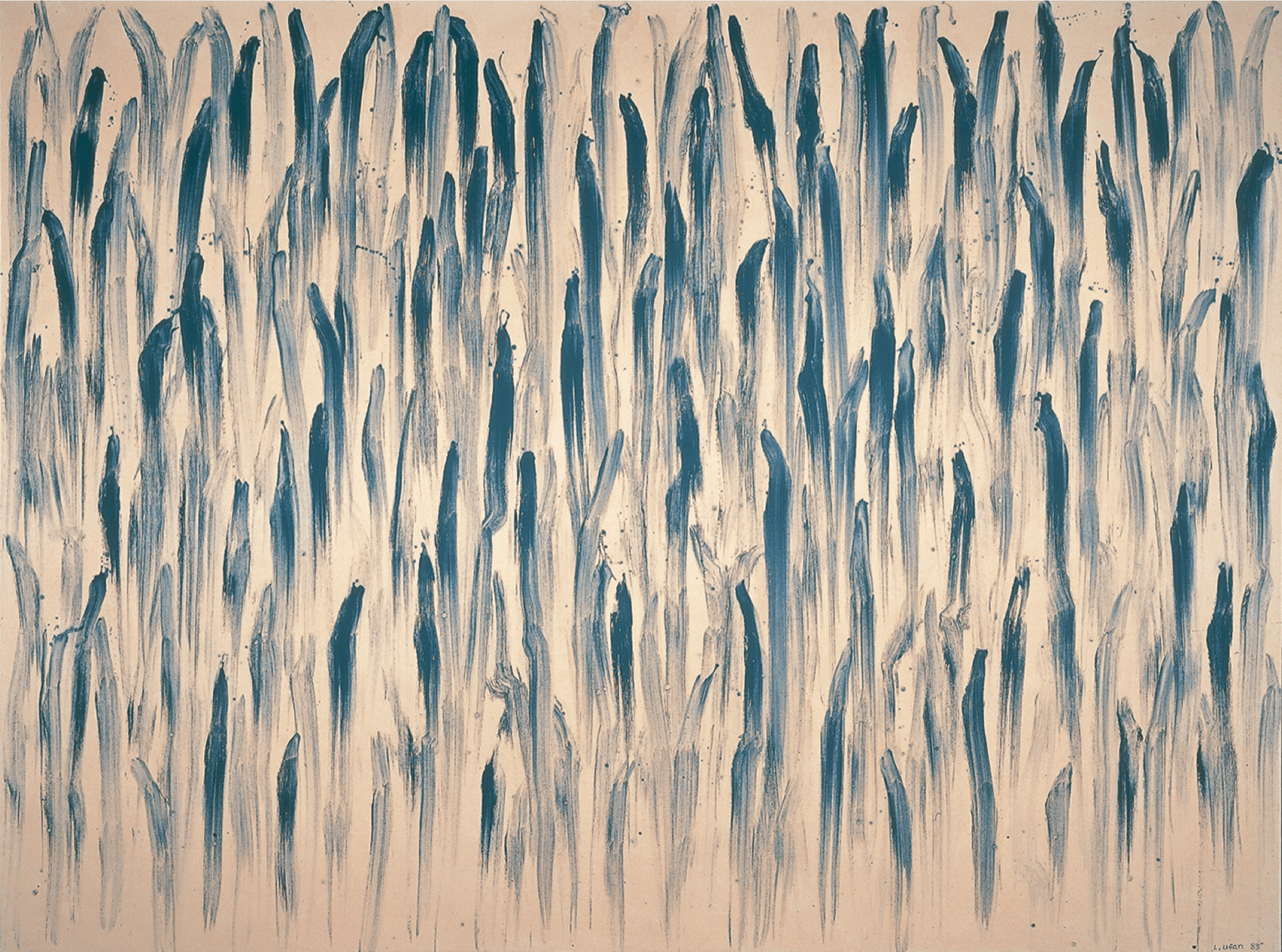

Born in Gyeongsangnam-do Korea and based in Japan for most of his creative career, Lee U-Fan(1936-)is an artist who has sought to connect directly to the substance of the world by creating works rooted in the relationship between the human being, the things of the world and the spaces in which they coexist, rather than creating works that attempt to duplicate some preconceived state of completion. The work From Line in the Kawamura collection is composed solely of the most basic element of painting: the line. In Lee’s own words, “The product of each single stroke of the brush must correspond to a living, breathing thing.” His is a creative process in which the relationship born at the moment of contact between the brush and the painting surface expands to define a unique consciousness and worldview.

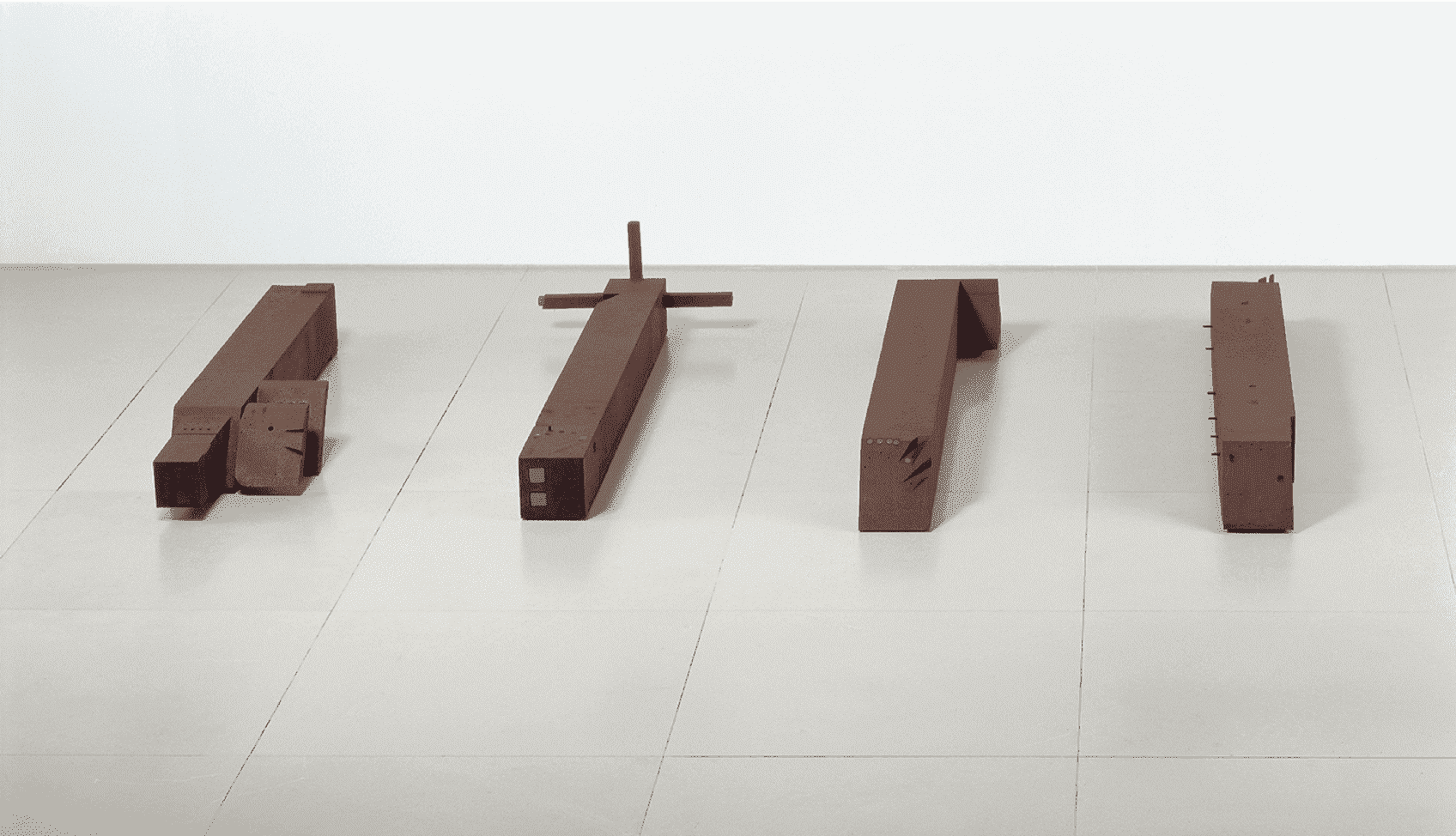

Oscillating Scale Ⅰ, 1979, 20.5 × 34.7 × 149.5cm / Oscillating Scale Ⅱ, 1979, 34.6 × 54.6 × 163.5cm

Oscillating Scale Ⅲ, 1979, 19.7 × 28.8 × 181.6cm / Oscillating Scale Ⅳ, 1979, 18.8 × 19.7 × 186.2cm

Isamu Wakabayashi (1936-2003) is an artist who created sculptures primarily of steel in his pursuit of space and time as it appears at the boundaries between humanity and the natural or material world. In his Oscillating Scale works, the artist represents the line of sight between the viewer and the object with bar-shaped forms constructed to serve as shaku or “scales” to measure the fluctuating space between person and object when the person tries to perceive and understand the object. The four Oscillating Scale constructions that make up this important work represent Wakabayashi’s decisive point of conclusion in his artistic quest.